Code

# load libraries for blog post

library(ggplot2)

library(plotly)

library(data.table)

library(kableExtra)

library(RColorBrewer) # for generating color palettesTomas Kristijonas Uždavinys

Invalid Date

The binomial test is a statistical test used to determine whether the proportion of cases in one of only two categories is equivalent to a pre-specified proportion. Categories could include the default rate of clients within the next 12 months, patients with high or low risk of heart disease, potential customers who are likely or not likely to make a purchase, or the rate of manufacturing defects. This widely used test finds applications in diverse fields, including credit risk, medicine, and manufacturing. It is also known to as the one-sample proportion test or test of one proportion.

As with all statistical tests, the binomial test has assumptions and conditions that must be met before applying it to real-life data:

The aim of this blog post is to showcase the ramifications of failing to meet “success-failure” condition critereon. Practical examples are coded in both R and Python languages.

Suppose that we have a sample where outcomes are binary - e.g. only “success” and “failure”. For the given sample, we would like to estimate the true proportion and also set up a statistical test to verify whether if the proportion is equal to some value, e.g. expected.

First, we calculate a point estimate:

\[p = \frac{n_s}{n}\]

, where \(n\) - sample size and \(n_s\) - the number of successful observations (or it can be the number of failures).

\[SE = \sqrt{\frac{p \cdot (1 - p)}{n}}\] , where \(SE\) is standard error. To perform a test, one first needs to derive a Null hypothesis:

\[H_0: p = p_0\]

and an alternative hypothesis:

Finally, we needs to calculate \(Z\) statistics:

\[Z = \frac{p_0-p}{SE}\]

Obtaining the value of \(Z\) enables us to either compute confidence intervals (\(CI\)) or reject \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_A\)

To approximate any distribution as normal, it is imperative to calculate the mean (\(\mu\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma\)). For the Binomial distribution, which consists of a number of experiments \(n\) and a probability \(p\), the mean of the normal distribution is:

\[\mu = n \cdot p\]

and the standard deviation:

\[\sigma = \sqrt{n \cdot p \cdot (1 - p)}.\]

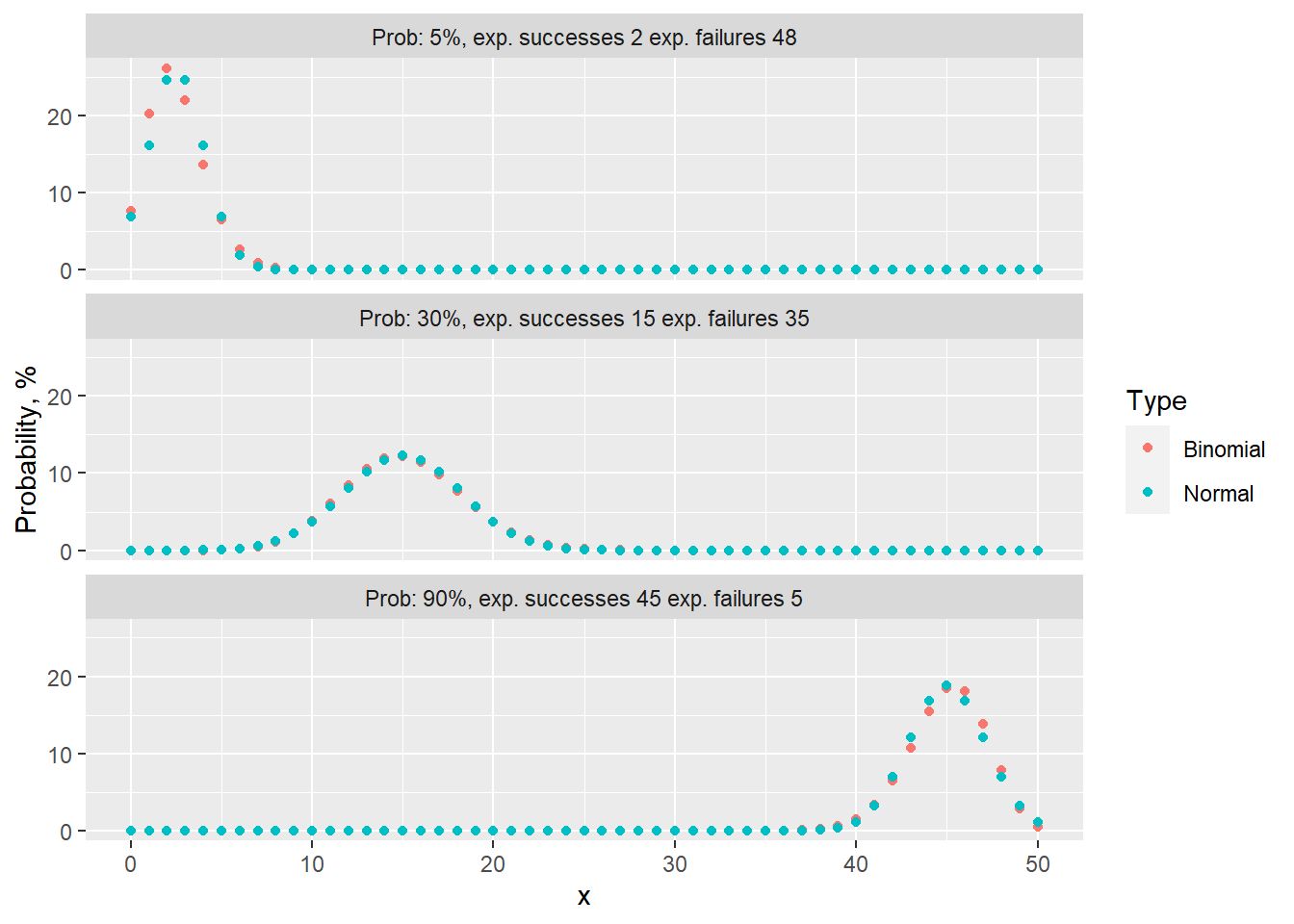

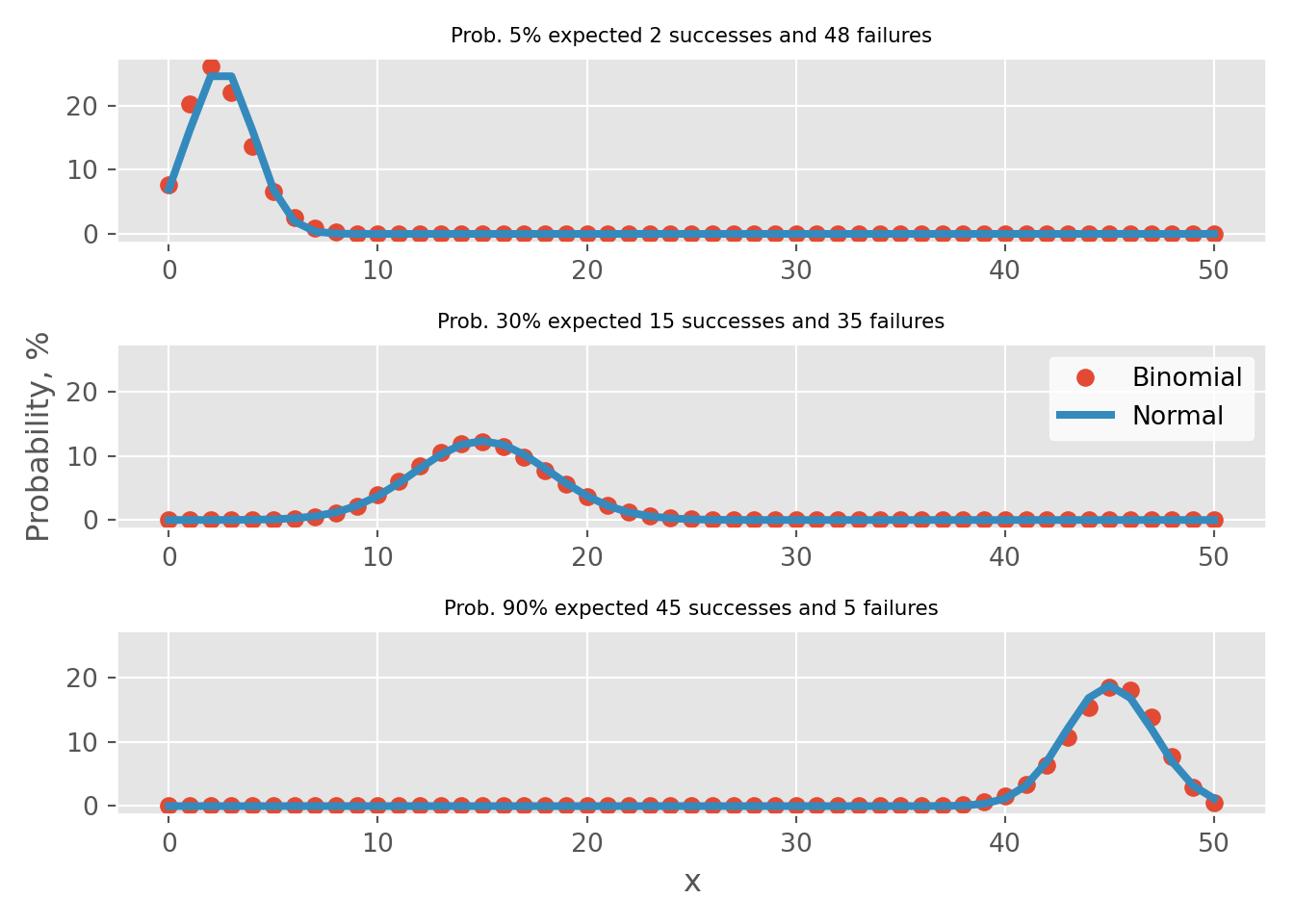

Meeting the “Success-Failure” condition is crucial to approximate Binomial distribution as Normal. Below, I present an instance of 50 Binomial events with varying probability rates of 5%, 30%, and 90%. In tabs binomial vs normal binomial distributions are plotted against it’s normal distribution approximation.

# probabilities

p <- c(0.05, 0.3, 0.9)

# successes

x <- 0:50

# create data.table

dt <- CJ(p, x)

# add size column

dt[, size := 50]

# add binomial probability

dt[, Binomial := dbinom(x, size=size, prob=p) * 100]

# create label column

dt[, label := paste0("Prob: ", round(p*100),

"%, exp. successes ", round(p*size),

" exp. failures ", round((1-p)*size))]

# calculate mean and standard deviation

dt[, mu := size * p]

dt[, st.dev := sqrt(p * (1 - p) * size)]

# get norm distribution

dt[, Normal := dnorm(x, mean=mu, sd = st.dev) * 100]

# convert to ordered factor

dt[, label := factor(label, levels=c("Prob: 5%, exp. successes 2 exp. failures 48",

"Prob: 30%, exp. successes 15 exp. failures 35",

"Prob: 90%, exp. successes 45 exp. failures 5" ))]

# reshape for plotting

dt.plot <- melt(dt, id.vars = c("x", "label"),

measure.vars = c("Binomial", "Normal"),

variable.name = c("Type"),

value.name = c('prob'))

# create figure

fig <- ggplot(dt.plot, aes(x, prob, color=Type)) + geom_point() + facet_wrap(~label, ncol = 1) + ylab("Probability, %")

fig

# probabilities

p = [0.05, 0.3, 0.9]

# successes

x = np.arange(51)

# create DataFrame with all combinations

df_1 = pd.DataFrame({'p': p})

df_2 = pd.DataFrame({'x': x})

# create key for joining

df_1['key'] = 0

df_2['key'] = 0

# perform cross join

df = df_1.merge(df_2, on='key', how='outer')

# drop key column

del df['key']

# add size value

df['size'] = 50

# calculate binomial probability

df['Binomial'] = binom.pmf(df['x'], df['size'], df['p']) * 100

# calculate mean and standard deviation

df['mu'] = df['size'] * df['p']

df['se'] = np.sqrt(df['p'] * (1 - df['p']) / df['size'])

df['std'] = np.sqrt(df['p'] * (1 - df['p']) * df['size'])

# get norm distribution

df['Normal'] = df.apply(lambda x: norm.pdf(x['x'], x['mu'], x['std']) * 100, axis = 1)

# create figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharey=True)

# iterate over probabilities

for i, _p in enumerate(p):

# select data for plotting

dt_plot = df.loc[df['p'] == _p].copy()

# plot binomial and normal distributions

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Binomial'], "o", label='Binomial');

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Normal'], "-", label='Normal', linewidth=3);

# add sub titles

ax[i].set_title(f"Prob. {_p*100:.0f}% expected {50*_p:.0f} successes and {50*(1-_p):.0f} failures", fontsize=8);

# add labels

ax[1].set_ylabel("Probability, %");

ax[2].set_xlabel("x");

# add legend and white background

legend = ax[1].legend(frameon = 1);

frame = legend.get_frame();

frame.set_color('white');

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# calculate error (use DataFrame from previous code chunk)

df['Error'] = df.Binomial - df.Normal

# create figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharey=True)

# iterate over probabilities

for i, _p in enumerate(p):

# select data for plotting

dt_plot = df.loc[df['p'] == _p]

# plot binomial and normal distributions

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Error'], "o", color='k', markersize=3);

# add sub titles

ax[i].set_title(f"Prob. {_p*100:.0f}% expected {50*_p:.0f} successes and {50*(1-_p):.0f} failures", fontsize=8);

# adjust limits for better readability

ax[0].set_ylim(-4.9, 4.9)

# add labels(-4.9, 4.9)

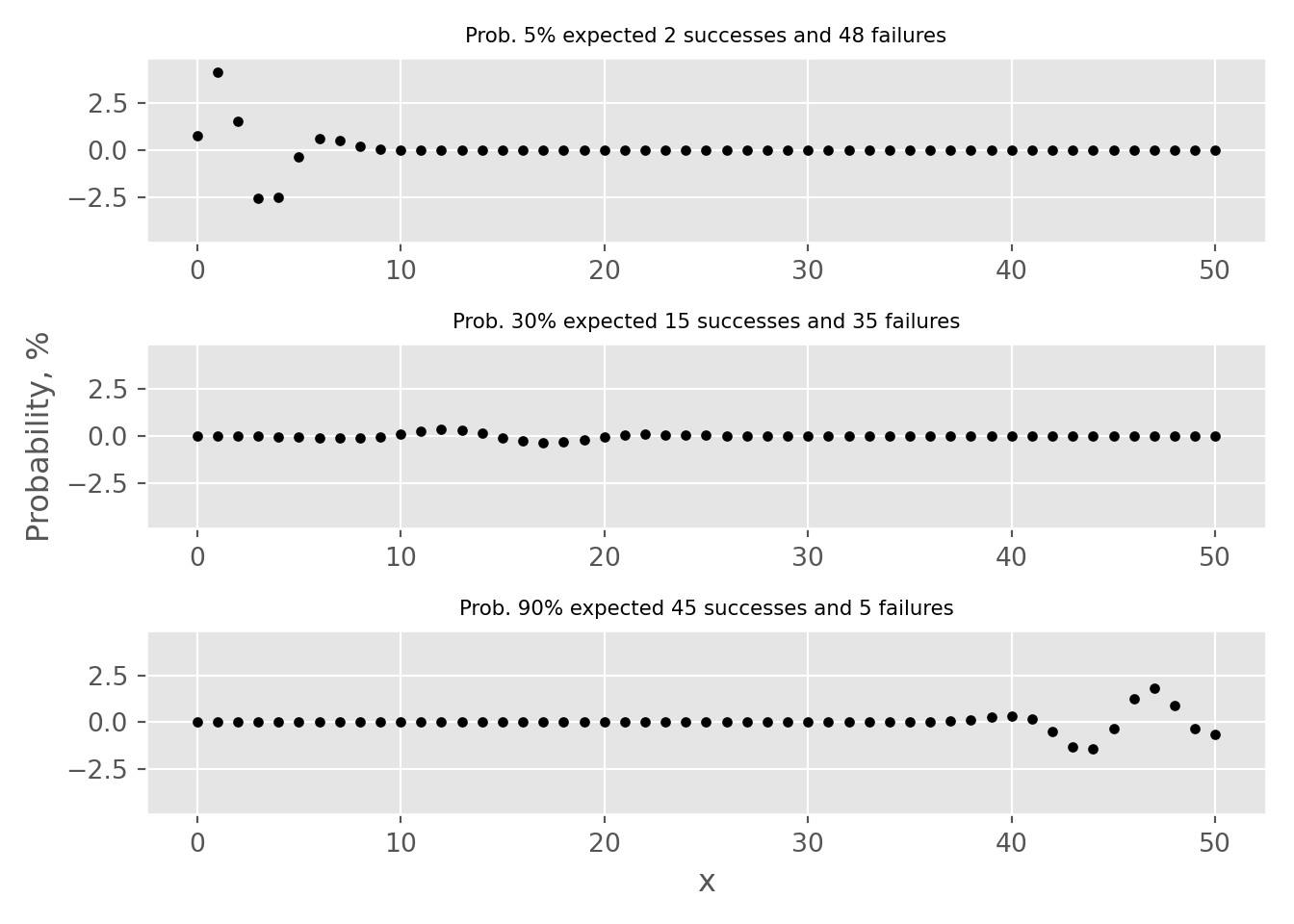

Out of 3 examples, the “Success-Failure” criterion is only applicable for the case where p=30%. By examining the error tabs, one can see that there is an approximation error. This refers to the disparity between the probabilities calculated using the Binomial and Normal distribution approximations. In particular, for the examples where p is set to 5% or 90%, this error can result in an overestimation or underestimation by more than 2% for point estimates.

To better understand approximation error, it’s important to consider the differences between the discrete binomial distribution and the continuous normal distribution. The binomial distribution represents the probability of getting k successes in n independent trials, each with probability p of success. Its probability space is bounded between 0 and k events, where k represents the number of attempts. In contrast, the normal distribution represents a continuous probability distribution of a random variable with an infinite range of possible values i.e. one can calculate probability to observer 2.5 successes after 10 trials. Furthermore, apart from the case where p=50%, the binomial distribution is not symmetrical, unlike the normal distribution. This means that the area under the curve on one side of the mean (expected number of successes) is not equal to the area under the curve on the other side.

Due to these differences, approximating the binomial distribution using the normal distribution will result in an approximation error. This error will be calculated as the difference between the probabilities calculated using the two distributions. In order to visualize approximation error, I will use interactive charts generated by the plotly library/package. Custom plotting functions were created in R and Python.

PlotDistributions <- function(prob, size){

# create observation vector

if (prob < 0.5){

x <- 0:(size*prob*3)

} else {

x <- (size - 3 * size * (1 - prob)):size

}

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x, size=size, prob=prob) * 100

y.norm <- dnorm(x, mean=size * prob, sd = sqrt(prob * (1 - prob) * size)) * 100

# create data table for plotting

dt <- data.table(x = x,

prob.binom = y.binom,

prob.norm = y.norm)

# add columns with hover information

dt[, text.1 := paste0('Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.binom, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.2 := paste0('Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.norm, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.3 := paste0('Point estimate error<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.binom - y.norm, 3), "%")]

# create figure

fig <- plot_ly(data = dt, type = 'scatter', mode = 'lines')

# add traces

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~prob.norm, text = ~text.1,

name = 'Normal',mode = 'lines',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "#FF6666", width = 5))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~prob.binom, text = ~text.2,

name = 'Binomial',mode = 'markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

marker = list(color = "#3399FF", size = 12))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~(prob.binom-prob.norm), text = ~text.3,

name = 'Error',mode = 'lines+markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "black", width = 5),

marker = list(color = "black", size = 12),

visible = "legendonly")

# update layout

fig <- fig %>% layout(title = paste0("p = ", round(prob*100), "%, ", size, " trials"),

xaxis = list(title = "Observations"),

yaxis = list (title = "Probability, %"),

hovermode = "x unified",

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Distributions </b>')))

# return figure

return(fig)

}# create function for plotting distributions

def plot_distributions(prob, size):

# create observation vector

x = np.arange(int(size*prob*3))

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y_binom = binom.pmf(x, n=size, p=prob) * 100

# calculate variance and sigma

variance = size * prob * (1 - prob)

sigma = np.sqrt(variance)

y_norm = norm.pdf(x, loc = size * prob, scale = sigma) * 100

# generate Data.Frame

df = pd.DataFrame({'x': x, 'binom': y_binom, 'norm': y_norm})

# calculate error

df['error'] = df.binom - df.norm

error = df.binom - df.norm

# generate hover messages

df['text_1'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["binom"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

df['text_2'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["norm"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

df['text_3'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate error<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["error"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

# create figure

fig = go.Figure()

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=y_norm, text = df['text_1'].values,

mode='lines', name='Normal', hoverinfo = 'text',

line=dict(color='#FF6666', width=5)))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=y_binom, text = df['text_2'].values,

mode='markers', name='Binomial', hoverinfo = 'text',

marker=dict(color='#3399FF', size=12)))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=error, text = df['text_3'].values,

mode='markers', name='Error', hoverinfo = 'text',

marker=dict(color='black', size=12),

visible = "legendonly"))

# Edit the layout

fig.update_layout(title=f"p = {prob*100:.1f}%, {size} trials",

xaxis_title='Observations',

yaxis_title='Probability, %',

template="ggplot2",

hovermode="x unified")

return figNext, I have provided examples using small probabilities of 99%, 95%, 0.5%, and 0.1% with either 5 expected failures or 5 expected successes. To view the distribution of errors, simply click on the error line on the chart legend.

Let’s say we have a hypothetical model with a small probability of occurrence, such as a 0.5% chance of manufacturing defects or a 0.5% chance of clients defaulting on their credit obligations. To meet the “Success-Failure” condition for this model, we would need to collect at least 2000 observations, i.e. manufacture 2000 devices or issue credit to 2000 obligators. In the 0.5% (Python) tab, one can see that if we have only collected 1000 events and expect 5 failures/defaults, normal distribution approximation overestimates the probability for \(\ge5\) and underestimates it for \(\le5\), as evident from visual inspection and reviewing error estimates for different outcomes (select error line on legend to view error distribution). For cases then we are very certain, e.g. 99.9% (R), overestimation if for cases \(\le5\) and underestimation for \(\ge5\). From visual inspection, one can observe that the smaller the probability, the larger the error between point estimates becomes.

Let’s try to quantify approximation error by calculating 3 probabilities using binomial and it’s approximation using normal distribution:

After calculating, these probabilities can be compared them by using ratios e.g. \(ratio_1 = \frac{p_1 (binom.)}{p_1 (norm.)}\). In the table below, \(p_1\) probabilities calculated using different distributions are presented. I also provide all 3 ratios, which shows by how much normal distribution overestimates/underestimates binomial distribution. For all cases 5 successes/failures are expected.

# generate data.table

dt <- data.table(p = c(0.999, 0.995, 0.99, 0.95, 0.8,

0.5,

0.2, 0.05, 0.01, 0.005, 0.001),

N = c(5000, 1000, 500, 100, 25,

10,

25, 100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# expected events

dt[, x := p * N]

# get binomial, normal probabilities and their ratio

dt[, binom.p1 := dbinom(x, size=N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[, norm.p1 := dnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

dt[, ratio.1 := binom.p1/norm.p1 * 100]

# calculate p2 probabilities

dt[, binom.p2 := pbinom(x-1, size=N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[, norm.p2 := (1-dnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)))/2 * 100]

# calculate p3 probabilities

dt[, binom.p3 := (1 - pbinom(x, size=N, prob=p)) * 100]

# calculate ratios

dt[, ratio.2 := binom.p2/norm.p2 * 100]

dt[, ratio.3 := binom.p3/norm.p2 * 100]

# round columns for better readability

cols <- names(dt)[4:11]

dt[,(cols) := round(.SD, 3), .SDcols=cols]

# convert probability to percents

dt[, p := round(p * 100, 1)]

# remove column

dt$x <- NULL

# generate table with first few rows and columns

knitr::kable(dt[, c(1:5, 9, 10)], col.names = c("p, %", "N", "p1 (binom.), %", "p1 (norm.), %", "ratio 1", "ratio 2", "ratio 3")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"))| p, % | N | p1 (binom.), % | p1 (norm.), % | ratio 1 | ratio 2 | ratio 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99.9 | 5000 | 17.556 | 17.850 | 98.349 | 93.497 | 107.220 |

| 99.5 | 1000 | 17.591 | 17.886 | 98.349 | 93.538 | 107.181 |

| 99.0 | 500 | 17.635 | 17.931 | 98.349 | 93.589 | 107.132 |

| 95.0 | 100 | 18.002 | 18.305 | 98.345 | 94.008 | 106.734 |

| 80.0 | 25 | 19.602 | 19.947 | 98.267 | 95.764 | 105.099 |

| 50.0 | 10 | 24.609 | 25.231 | 97.535 | 100.832 | 100.832 |

| 20.0 | 25 | 19.602 | 19.947 | 98.267 | 105.099 | 95.764 |

| 5.0 | 100 | 18.002 | 18.305 | 98.345 | 106.734 | 94.008 |

| 1.0 | 500 | 17.635 | 17.931 | 98.349 | 107.132 | 93.589 |

| 0.5 | 1000 | 17.591 | 17.886 | 98.349 | 107.181 | 93.538 |

| 0.1 | 5000 | 17.556 | 17.850 | 98.349 | 107.220 | 93.497 |

There results show that when \(p > 50\%\) overestimation is observed on the right-hand side of distribution and opposite is true for \(p < 50\%\). The ratio between \(p_1\) probabilities is the same across all examples - it is defined by number of expected outcomes and not probability. Overestimation \(ratio_2>100\%\) are the same for \(p > 50\%\) cases as underestimation \(ratio_3<100\%\). As implied probability becomes closer to 50%, the binomial distribution becomes more symmetrical so both \(ratio_2\) and \(ratio_3\) becomes closer to 100%.

Another way to measure approximation error is to calculate the total absolute approximation error, which is obtained by subtracting the normal distribution approximation from the binomial distribution approximation. The reason for using total error instead of the mean absolute error is that for the latter calculations are affected by very small errors at the edge of distributions. The key idea is that as the number of observations, i.e. the expected number of successes/failures increases, the total error between point estimates will decrease. Similar to the previous example, the total approximation error is calculated for the same probabilities with 5 expected successes/failures.

# generate data.table

dt <- data.table(p = c(0.999, 0.995, 0.99, 0.95, 0.8,

0.5,

0.2, 0.05, 0.01, 0.005, 0.001),

N = c(5000, 1000, 500, 100, 25,

10,

25, 100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# expected events

dt[, x := p * N]

# ugly, but quick way to calculate approximation error

for (p.tmp in dt$p){

# generate vector

x.vect <- 0:dt[p == p.tmp, N]

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x.vect, dt[p == p.tmp, N], p.tmp)

y.norm <- dnorm(x.vect, mean=dt[p == p.tmp, N] * p.tmp, sd = sqrt(p.tmp * (1 - p.tmp) * dt[p == p.tmp, N]))

# sum absolute error

y.err <- sum(abs(y.binom - y.norm))

# add error term

dt[p == p.tmp, tot.abs.error := round(y.err*100, 3)]

}

# convert probability to percents

dt[, p := round(p * 100, 1)]

# remove column

dt$x <- NULL

# generate table with first few rows and columns

knitr::kable(dt, col.names = c("p, %", "N", "Total absolute error, %")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"))| p, % | N | Total absolute error, % |

|---|---|---|

| 99.9 | 5000 | 10.804 |

| 99.5 | 1000 | 10.754 |

| 99.0 | 500 | 10.691 |

| 95.0 | 100 | 10.158 |

| 80.0 | 25 | 7.686 |

| 50.0 | 10 | 2.381 |

| 20.0 | 25 | 7.686 |

| 5.0 | 100 | 10.158 |

| 1.0 | 500 | 10.691 |

| 0.5 | 1000 | 10.754 |

| 0.1 | 5000 | 10.804 |

The table above shows that the total point approximation error is the smallest when the probability is the largest (p=50%). However, for situations that are very likely, e.g. 99.9%, or very unlikely (0.1%), where we expect to see only a few successes or failures out of a large number of trials, approximating the binomial distribution with normal distribution can lead to more than 10% total point estimate error.

Next, let’s compare cumulative probabilities for different examples based on both probabilities (p) and expected values (EV). To highlight commonly used two-sided null hypothesis rejection levels, I have added 95% confidence intervals (black dashed line) and 99% confidence intervals (red dashed line).

# helper function for plotting

vline <- function(x = 0, color = "black") {

list(

type = "line",

y0 = 0,

y1 = 1,

yref = "paper",

x0 = x,

x1 = x,

line = list(color = color, dash = "dot")

)

}

# helper function to draw cum. probabilities

PlotCumProbs <- function(p, N){

# for adjusting plot x limits

x.ratio <- p*N

# create vector depending on probability

if (p <= 0.5){

if (N*p >= 10){

x <- 0:max((N*p*2), N*p)

} else {

x <- 0:max((N*p*3), N*p)

}

} else {

if (N*(1-p) >= 10){

x <- max((N - 2 * N * (1 - p)), 0):N

} else {

x <- max((N - 3 * N * (1 - p)), 0):N

}

}

# calculate z values as events for different confidence intervals

Z.95.left <- (N * p - 1.960 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.99.left <- (N * p - 2.576 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.95.right <- (N * p + 1.960 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.99.right <- (N * p + 2.576 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

# calculate cum. probabilities for both binomial and normal distributions

y.binom <- pbinom(x, size=N, prob=p) * 100

y.norm <- pnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100

# create data.table for plotting

dt <- data.table(x = x, y.binom = y.binom, y.norm = y.norm)

# calculate error

dt[, error := y.binom - y.norm]

# add hover text messages

dt[, text.1 := paste0(round(y.binom, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.2 := paste0(round(y.norm, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.3 := paste0(round(error, 3), "%")]

# create figure

fig <- plot_ly(data = dt, type = 'scatter', mode = 'lines')

# add traces

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~y.norm, text = ~text.1,

name = 'Normal',mode = 'lines',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "#FF6666", width = 5))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~y.binom, text = ~text.2,

name = 'Binomial',mode = 'markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

marker = list(color = "#3399FF", size = 12))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~error, text = ~text.3,

name = 'Error',mode = 'lines+markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "black", width = 5),

marker = list(color = "black", size = 12))

# update layout

fig <- fig %>% layout(title = paste0("p = ", round(p*100, 1), "%, ", N, " trials (EV = ", x.ratio, ")"),

xaxis = list(title = "Observations"),

yaxis = list (title = "Probability, %"),

hovermode = "x unified",

shapes = list(vline(Z.99.left, color='red'), vline(Z.95.left), vline(Z.95.right), vline(Z.99.right, color='red')),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Distributions </b>')))

# return figure object

return(fig)

}

# plot example for 0.1%

PlotCumProbs(0.001, 5000)The first thing to note is that it’s not possible to test a 2-sided hypothesis for a low EV example. Take a look at the tabs with “(5 EV)” in their name - the red dashed lines fall outside the range of viable outcomes, except for 50% (5EV) case. In this example, if you conduct 10 trials and observe either 0 or 10 successes, you can reject the null hypothesis \(H_0 \ne p\) with a 99% confidence interval. However, as the sample size increases i.e. one gets larger EV, the distribution widths become narrower. This means that 2-sided tests with a 99% confidence interval become viable for other probability values, as seen in the example with an 20% (15 EV). Additionally, when comparing distributions with the same EV but different probabilities, we see that the error between the binomial distribution and its approximation using the normal distribution is very similar.

Finally, let’s now explore how much \(ratio_1\) and total absolute approximation errors are affected by the sample size. In the examples below, the sample sizes were adjusted based on the number of expected successes/failures. For instance, to observe 5 EV with p=1%, one needs 500 observations and for p=20%, one needs 25 observations. However, this approach has some drawbacks, such as being difficult to normalize for specific cases. For example, to observe 7 EV with p=15%, one needs 46.66 observations. In such cases, the number of observations was rounded down to the nearest integer, resulting in some spiky line charts for these specific cases.

# generate data.table with expected values and sample probabilities

probs <- c(0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.99, 0.999)

dt <- CJ(Sucesses = c(1:50), p = probs)

# get probability and sample size for expected values

dt[p <= 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / p)]

dt[p > 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / (1 - p))]

# get number of failures

dt[, Failures := N - Sucesses]

# calculate probabilities to observe expected number of observations

dt[p <= 0.5, binom.p1 := dbinom(Sucesses, size = N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[p > 0.5, binom.p1 := dbinom(Failures, size = N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[p <= 0.5, norm.p1 := dnorm(Sucesses, mean = N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

dt[p > 0.5, norm.p1 := dnorm(Failures, mean = N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

# get ratio between point estimates

dt[, ratio.1 := round(binom.p1/norm.p1 * 100, 3)]

# for coloring get probability

dt[, Probability := paste0(round(p * 100, 1), "%")]

# text message for hover (decided not to use this column)

dt[, text := paste0(Probability, " with ", N, " attempts: ", ratio.1)]

# generate color palette

# code example taken from

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15282580/how-to-generate-a-number-of-most-distinctive-colors-in-r

n <- length(probs)

qual_col_pals = brewer.pal.info[brewer.pal.info$category == 'qual',]

col_vector = unlist(mapply(brewer.pal, qual_col_pals$maxcolors, rownames(qual_col_pals)))

# generate figure

fig <- plot_ly(dt,

x = ~Sucesses,

y = ~ratio.1,

color = ~Probability,

colors = col_vector,

line = list(width = 4))

fig <- fig %>% add_lines()

# with log scales

fig <- layout(fig,

hovermode = "x unified",

yaxis = list(type = "log", title = "Ratio 1, %"),

xaxis = list(title = "Expected sucessess/failures"),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Probabilities </b>')))

fig# generate data.table with expected values and sample probabilities

probs <- c(0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.99, 0.999)

dt <- CJ(Sucesses = c(1:100), p = probs)

# get probability and sample size for expected values

dt[p <= 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / p)]

dt[p > 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / (1 - p))]

# get number of failures

dt[, Failures := N - Sucesses]

# ugly, but quick way to calculate approximation error

for (idx in 1:nrow(dt)){

# generate vector

x.vect <- 0:dt[idx, N]

# select probaiblity

p.tmp <- dt[idx, p]

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x.vect, dt[idx, N], p.tmp)

y.norm <- dnorm(x.vect, mean=dt[idx, N] * p.tmp, sd = sqrt(p.tmp * (1 - p.tmp) * dt[idx, N]))

# sum absolute error

y.err <- sum(abs(y.binom - y.norm))

# add error term

dt[idx, tot.abs.error := round(y.err*100, 3)]

}

# generate color palette

# code example taken from

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15282580/how-to-generate-a-number-of-most-distinctive-colors-in-r

n <- length(probs)

qual_col_pals = brewer.pal.info[brewer.pal.info$category == 'qual',]

col_vector = unlist(mapply(brewer.pal, qual_col_pals$maxcolors, rownames(qual_col_pals)))

# for coloring get probability

dt[, Probability := paste0(round(p * 100, 1), "%")]

# generate figure

fig <- plot_ly(dt,

x = ~Sucesses,

y = ~tot.abs.error,

color = ~Probability,

colors = col_vector,

line = list(width = 4))

fig <- fig %>% add_lines()

# with log scales

fig <- layout(fig,

hovermode = "x unified",

yaxis = list(type = "log", title = "Total absolute error, %"),

xaxis = list(title = "Expected sucessess/failures"),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Probabilities </b>')))

figSurprisingly the \(ratio_1\) is inversely depended on probability - approximation error is the smallest for very likely or unluckily cases. The opposite is true for total absolute error - it is the smallest for p=50%. Even with 50 EV for small probabilities, i.e. 0.1% or 99.9% this error \(>3.5\%\). The key take away is that if we are looking ar large confidence intervals (CI), i.e. 95% or 99%, then 10 EV is sufficient to test hypothesis. If we would like to establish some intermediate values between, then for small probabilities, number of observations to collect should increased.

One should be very mindful when designing experiments for one-sample binomial test. Failing to meet “success-failure” condition would result in overestimation or underestimation of you \(H_0\) hypothesis results. For relatively large probabilities, 30%-70% one can use

Content for this blog post was prepared using following resources:

---

title: "One-Sample Binomial Test (Part 1)"

author: "Tomas Kristijonas Uždavinys"

format:

html:

code-fold: true

code-tools: true

date: "2023-04-XX"

draft: false

categories: [R, Python, Statistics]

---

## Introduction

The binomial test is a statistical test used to determine whether the proportion of cases in one of only two categories is equivalent to a pre-specified proportion. Categories could include the default rate of clients within the next 12 months, patients with high or low risk of heart disease, potential customers who are likely or not likely to make a purchase, or the rate of manufacturing defects. This widely used test finds applications in diverse fields, including credit risk, medicine, and manufacturing. It is also known to as the **one-sample proportion test** or **test of one proportion**.

As with all statistical tests, the binomial test has assumptions and conditions that must be met before applying it to real-life data:

- The "success-failure" condition requires observing a minimum of **n** successes and **n** failures in the sample;

- observations are independent, i.e. the occurrence of one event does not affect the probability of occurrence of the other.

The aim of this blog post is to showcase the ramifications of failing to meet "success-failure" condition critereon. Practical examples are coded in both `R` and `Python` languages.

::: panel-tabset

## R

```{r}

#| warning: false

# load libraries for blog post

library(ggplot2)

library(plotly)

library(data.table)

library(kableExtra)

library(RColorBrewer) # for generating color palettes

```

## Python

```{python}

# load packages for blog post

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import plotly.graph_objects as go

from scipy.stats import binom, norm

# set style

plt.style.use("ggplot")

```

:::

## Theory

Suppose that we have a sample where outcomes are binary - e.g. only "success" and "failure". For the given sample, we would like to estimate the true proportion and also set up a statistical test to verify whether if the proportion is equal to some value, e.g. expected.

First, we calculate a point estimate:

$$p = \frac{n_s}{n}$$

, where $n$ - sample size and $n_s$ - the number of successful observations (or it can be the number of failures).

$$SE = \sqrt{\frac{p \cdot (1 - p)}{n}}$$ , where $SE$ is standard error. To perform a test, one first needs to derive a Null hypothesis:

$$H_0: p = p_0$$

and an alternative hypothesis:

- one-sided $H_A: p < p_0$ or $H_A: p > p_0$,

- two-sided $H_A: p \ne p_0$.

Finally, we needs to calculate $Z$ statistics:

$$Z = \frac{p_0-p}{SE}$$

Obtaining the value of $Z$ enables us to either compute confidence intervals ($CI$) or reject $H_0$ in favor of $H_A$

## "Success-failure" condition

To approximate any distribution as normal, it is imperative to calculate the mean ($\mu$) and standard deviation ($\sigma$). For the Binomial distribution, which consists of a number of experiments $n$ and a probability $p$, the mean of the normal distribution is:

$$\mu = n \cdot p$$

and the standard deviation:

$$\sigma = \sqrt{n \cdot p \cdot (1 - p)}.$$

Meeting the "Success-Failure" condition is crucial to approximate Binomial distribution as Normal. Below, I present an instance of 50 Binomial events with varying probability rates of 5%, 30%, and 90%. In tabs `binomial vs normal` binomial distributions are plotted against it's normal distribution approximation.

::: panel-tabset

## binomial vs. normal (R)

```{r}

# probabilities

p <- c(0.05, 0.3, 0.9)

# successes

x <- 0:50

# create data.table

dt <- CJ(p, x)

# add size column

dt[, size := 50]

# add binomial probability

dt[, Binomial := dbinom(x, size=size, prob=p) * 100]

# create label column

dt[, label := paste0("Prob: ", round(p*100),

"%, exp. successes ", round(p*size),

" exp. failures ", round((1-p)*size))]

# calculate mean and standard deviation

dt[, mu := size * p]

dt[, st.dev := sqrt(p * (1 - p) * size)]

# get norm distribution

dt[, Normal := dnorm(x, mean=mu, sd = st.dev) * 100]

# convert to ordered factor

dt[, label := factor(label, levels=c("Prob: 5%, exp. successes 2 exp. failures 48",

"Prob: 30%, exp. successes 15 exp. failures 35",

"Prob: 90%, exp. successes 45 exp. failures 5" ))]

# reshape for plotting

dt.plot <- melt(dt, id.vars = c("x", "label"),

measure.vars = c("Binomial", "Normal"),

variable.name = c("Type"),

value.name = c('prob'))

# create figure

fig <- ggplot(dt.plot, aes(x, prob, color=Type)) + geom_point() + facet_wrap(~label, ncol = 1) + ylab("Probability, %")

fig

```

## error (R)

```{r}

# calculate error (use data.table from previous code chunk)

dt[, Error := Binomial - Normal]

# create figure

fig <- ggplot(dt, aes(x, Error)) + geom_point() + facet_wrap(~label, ncol = 1) + ylab("Error (binom. - norm.), %")

fig

```

## binomial vs. normal (Python)

```{python}

# probabilities

p = [0.05, 0.3, 0.9]

# successes

x = np.arange(51)

# create DataFrame with all combinations

df_1 = pd.DataFrame({'p': p})

df_2 = pd.DataFrame({'x': x})

# create key for joining

df_1['key'] = 0

df_2['key'] = 0

# perform cross join

df = df_1.merge(df_2, on='key', how='outer')

# drop key column

del df['key']

# add size value

df['size'] = 50

# calculate binomial probability

df['Binomial'] = binom.pmf(df['x'], df['size'], df['p']) * 100

# calculate mean and standard deviation

df['mu'] = df['size'] * df['p']

df['se'] = np.sqrt(df['p'] * (1 - df['p']) / df['size'])

df['std'] = np.sqrt(df['p'] * (1 - df['p']) * df['size'])

# get norm distribution

df['Normal'] = df.apply(lambda x: norm.pdf(x['x'], x['mu'], x['std']) * 100, axis = 1)

# create figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharey=True)

# iterate over probabilities

for i, _p in enumerate(p):

# select data for plotting

dt_plot = df.loc[df['p'] == _p].copy()

# plot binomial and normal distributions

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Binomial'], "o", label='Binomial');

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Normal'], "-", label='Normal', linewidth=3);

# add sub titles

ax[i].set_title(f"Prob. {_p*100:.0f}% expected {50*_p:.0f} successes and {50*(1-_p):.0f} failures", fontsize=8);

# add labels

ax[1].set_ylabel("Probability, %");

ax[2].set_xlabel("x");

# add legend and white background

legend = ax[1].legend(frameon = 1);

frame = legend.get_frame();

frame.set_color('white');

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

## error (Python)

```{python}

# calculate error (use DataFrame from previous code chunk)

df['Error'] = df.Binomial - df.Normal

# create figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharey=True)

# iterate over probabilities

for i, _p in enumerate(p):

# select data for plotting

dt_plot = df.loc[df['p'] == _p]

# plot binomial and normal distributions

ax[i].plot(dt_plot['x'], dt_plot['Error'], "o", color='k', markersize=3);

# add sub titles

ax[i].set_title(f"Prob. {_p*100:.0f}% expected {50*_p:.0f} successes and {50*(1-_p):.0f} failures", fontsize=8);

# adjust limits for better readability

ax[0].set_ylim(-4.9, 4.9)

# add labels

ax[1].set_ylabel("Probability, %")

ax[2].set_xlabel("x")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

:::

Out of 3 examples, the "Success-Failure" criterion is only applicable for the case where p=30%. By examining the `error` tabs, one can see that there is an approximation error. This refers to the disparity between the probabilities calculated using the Binomial and Normal distribution approximations. In particular, for the examples where p is set to 5% or 90%, this error can result in an overestimation or underestimation by more than 2% for point estimates.

## Estimating approximation error

To better understand approximation error, it's important to consider the differences between the discrete binomial distribution and the continuous normal distribution. The binomial distribution represents the probability of getting `k` successes in `n` independent trials, each with probability p of success. Its probability space is bounded between 0 and `k` events, where `k` represents the number of attempts. In contrast, the normal distribution represents a continuous probability distribution of a random variable with an infinite range of possible values i.e. one can calculate probability to observer 2.5 successes after 10 trials. Furthermore, apart from the case where p=50%, the binomial distribution is not symmetrical, unlike the normal distribution. This means that the area under the curve on one side of the mean (expected number of successes) is not equal to the area under the curve on the other side.

Due to these differences, approximating the binomial distribution using the normal distribution will result in an approximation error. This error will be calculated as the difference between the probabilities calculated using the two distributions. In order to visualize approximation error, I will use interactive charts generated by the `plotly` library/package. Custom plotting functions were created in `R` and `Python`.

::: panel-tabset

## plot_ly function (R)

```{r}

PlotDistributions <- function(prob, size){

# create observation vector

if (prob < 0.5){

x <- 0:(size*prob*3)

} else {

x <- (size - 3 * size * (1 - prob)):size

}

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x, size=size, prob=prob) * 100

y.norm <- dnorm(x, mean=size * prob, sd = sqrt(prob * (1 - prob) * size)) * 100

# create data table for plotting

dt <- data.table(x = x,

prob.binom = y.binom,

prob.norm = y.norm)

# add columns with hover information

dt[, text.1 := paste0('Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.binom, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.2 := paste0('Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.norm, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.3 := paste0('Point estimate error<br>to observer exactly ', x,

' events is ', round(y.binom - y.norm, 3), "%")]

# create figure

fig <- plot_ly(data = dt, type = 'scatter', mode = 'lines')

# add traces

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~prob.norm, text = ~text.1,

name = 'Normal',mode = 'lines',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "#FF6666", width = 5))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~prob.binom, text = ~text.2,

name = 'Binomial',mode = 'markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

marker = list(color = "#3399FF", size = 12))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~(prob.binom-prob.norm), text = ~text.3,

name = 'Error',mode = 'lines+markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "black", width = 5),

marker = list(color = "black", size = 12),

visible = "legendonly")

# update layout

fig <- fig %>% layout(title = paste0("p = ", round(prob*100), "%, ", size, " trials"),

xaxis = list(title = "Observations"),

yaxis = list (title = "Probability, %"),

hovermode = "x unified",

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Distributions </b>')))

# return figure

return(fig)

}

```

## plotly function (Python)

```{python}

# create function for plotting distributions

def plot_distributions(prob, size):

# create observation vector

x = np.arange(int(size*prob*3))

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y_binom = binom.pmf(x, n=size, p=prob) * 100

# calculate variance and sigma

variance = size * prob * (1 - prob)

sigma = np.sqrt(variance)

y_norm = norm.pdf(x, loc = size * prob, scale = sigma) * 100

# generate Data.Frame

df = pd.DataFrame({'x': x, 'binom': y_binom, 'norm': y_norm})

# calculate error

df['error'] = df.binom - df.norm

error = df.binom - df.norm

# generate hover messages

df['text_1'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["binom"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

df['text_2'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate probability<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["norm"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

df['text_3'] = df.apply(lambda x: f'Point estimate error<br>to observer exactly {x["x"]:.0f} events is {x["error"]:.3f}%', axis = 1)

# create figure

fig = go.Figure()

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=y_norm, text = df['text_1'].values,

mode='lines', name='Normal', hoverinfo = 'text',

line=dict(color='#FF6666', width=5)))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=y_binom, text = df['text_2'].values,

mode='markers', name='Binomial', hoverinfo = 'text',

marker=dict(color='#3399FF', size=12)))

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=error, text = df['text_3'].values,

mode='markers', name='Error', hoverinfo = 'text',

marker=dict(color='black', size=12),

visible = "legendonly"))

# Edit the layout

fig.update_layout(title=f"p = {prob*100:.1f}%, {size} trials",

xaxis_title='Observations',

yaxis_title='Probability, %',

template="ggplot2",

hovermode="x unified")

return fig

```

:::

Next, I have provided examples using small probabilities of 99%, 95%, 0.5%, and 0.1% with either 5 expected failures or 5 expected successes. To view the distribution of errors, simply click on the `error` line on the chart legend.

::: panel-tabset

## 99.9% (R)

```{r}

# return figure

PlotDistributions(0.999, 5000)

```

## 99.5% (R)

```{r}

# return figure

PlotDistributions(0.995, 1000)

```

## 0.5% (Python)

```{python}

# use python helper function from above

fig = plot_distributions(0.005, 1000)

fig

```

## 0.01% (Python)

```{python}

# use python helper function from above

fig = plot_distributions(0.001, 5000)

fig

```

:::

Let's say we have a hypothetical model with a small probability of occurrence, such as a 0.5% chance of manufacturing defects or a 0.5% chance of clients defaulting on their credit obligations. To meet the "Success-Failure" condition for this model, we would need to collect at least 2000 observations, i.e. manufacture 2000 devices or issue credit to 2000 obligators. In the `0.5% (Python)` tab, one can see that if we have only collected 1000 events and expect 5 failures/defaults, normal distribution approximation overestimates the probability for $\ge5$ and underestimates it for $\le5$, as evident from visual inspection and reviewing error estimates for different outcomes (select `error` line on legend to view error distribution). For cases then we are very certain, e.g. `99.9% (R)`, overestimation if for cases $\le5$ and underestimation for $\ge5$. From visual inspection, one can observe that the smaller the probability, the larger the error between point estimates becomes.

Let's try to quantify approximation error by calculating 3 probabilities using binomial and it's approximation using normal distribution:

- $p_1$ to observe expected number of occurrences,

- $p_2$ to observe more than expected number of occurrences,

- $p_3$ to observe less than expected number of occurrences.

After calculating, these probabilities can be compared them by using ratios e.g. $ratio_1 = \frac{p_1 (binom.)}{p_1 (norm.)}$. In the table below, $p_1$ probabilities calculated using different distributions are presented. I also provide all 3 ratios, which shows by how much normal distribution overestimates/underestimates binomial distribution. For all cases 5 successes/failures are expected.

```{r}

# generate data.table

dt <- data.table(p = c(0.999, 0.995, 0.99, 0.95, 0.8,

0.5,

0.2, 0.05, 0.01, 0.005, 0.001),

N = c(5000, 1000, 500, 100, 25,

10,

25, 100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# expected events

dt[, x := p * N]

# get binomial, normal probabilities and their ratio

dt[, binom.p1 := dbinom(x, size=N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[, norm.p1 := dnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

dt[, ratio.1 := binom.p1/norm.p1 * 100]

# calculate p2 probabilities

dt[, binom.p2 := pbinom(x-1, size=N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[, norm.p2 := (1-dnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)))/2 * 100]

# calculate p3 probabilities

dt[, binom.p3 := (1 - pbinom(x, size=N, prob=p)) * 100]

# calculate ratios

dt[, ratio.2 := binom.p2/norm.p2 * 100]

dt[, ratio.3 := binom.p3/norm.p2 * 100]

# round columns for better readability

cols <- names(dt)[4:11]

dt[,(cols) := round(.SD, 3), .SDcols=cols]

# convert probability to percents

dt[, p := round(p * 100, 1)]

# remove column

dt$x <- NULL

# generate table with first few rows and columns

knitr::kable(dt[, c(1:5, 9, 10)], col.names = c("p, %", "N", "p1 (binom.), %", "p1 (norm.), %", "ratio 1", "ratio 2", "ratio 3")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"))

```

There results show that when $p > 50\%$ overestimation is observed on the right-hand side of distribution and opposite is true for $p < 50\%$. The ratio between $p_1$ probabilities is the same across all examples - it is defined by number of expected outcomes and not probability. Overestimation $ratio_2>100\%$ are the same for $p > 50\%$ cases as underestimation $ratio_3<100\%$. As implied probability becomes closer to 50%, the binomial distribution becomes more symmetrical so both $ratio_2$ and $ratio_3$ becomes closer to 100%.

Another way to measure approximation error is to calculate the total absolute approximation error, which is obtained by subtracting the normal distribution approximation from the binomial distribution approximation. The reason for using total error instead of the mean absolute error is that for the latter calculations are affected by very small errors at the edge of distributions. The key idea is that as the number of observations, i.e. the expected number of successes/failures increases, the total error between point estimates will decrease. Similar to the previous example, the total approximation error is calculated for the same probabilities with 5 expected successes/failures.

```{r}

# generate data.table

dt <- data.table(p = c(0.999, 0.995, 0.99, 0.95, 0.8,

0.5,

0.2, 0.05, 0.01, 0.005, 0.001),

N = c(5000, 1000, 500, 100, 25,

10,

25, 100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# expected events

dt[, x := p * N]

# ugly, but quick way to calculate approximation error

for (p.tmp in dt$p){

# generate vector

x.vect <- 0:dt[p == p.tmp, N]

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x.vect, dt[p == p.tmp, N], p.tmp)

y.norm <- dnorm(x.vect, mean=dt[p == p.tmp, N] * p.tmp, sd = sqrt(p.tmp * (1 - p.tmp) * dt[p == p.tmp, N]))

# sum absolute error

y.err <- sum(abs(y.binom - y.norm))

# add error term

dt[p == p.tmp, tot.abs.error := round(y.err*100, 3)]

}

# convert probability to percents

dt[, p := round(p * 100, 1)]

# remove column

dt$x <- NULL

# generate table with first few rows and columns

knitr::kable(dt, col.names = c("p, %", "N", "Total absolute error, %")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"))

```

The table above shows that the total point approximation error is the smallest when the probability is the largest (p=50%). However, for situations that are very likely, e.g. 99.9%, or very unlikely (0.1%), where we expect to see only a few successes or failures out of a large number of trials, approximating the binomial distribution with normal distribution can lead to more than 10% total point estimate error.

Next, let's compare cumulative probabilities for different examples based on both probabilities (p) and expected values (EV). To highlight commonly used two-sided null hypothesis rejection levels, I have added 95% confidence intervals (black dashed line) and 99% confidence intervals (red dashed line).

::: panel-tabset

## 0.1% (5 EV)

```{r}

# helper function for plotting

vline <- function(x = 0, color = "black") {

list(

type = "line",

y0 = 0,

y1 = 1,

yref = "paper",

x0 = x,

x1 = x,

line = list(color = color, dash = "dot")

)

}

# helper function to draw cum. probabilities

PlotCumProbs <- function(p, N){

# for adjusting plot x limits

x.ratio <- p*N

# create vector depending on probability

if (p <= 0.5){

if (N*p >= 10){

x <- 0:max((N*p*2), N*p)

} else {

x <- 0:max((N*p*3), N*p)

}

} else {

if (N*(1-p) >= 10){

x <- max((N - 2 * N * (1 - p)), 0):N

} else {

x <- max((N - 3 * N * (1 - p)), 0):N

}

}

# calculate z values as events for different confidence intervals

Z.95.left <- (N * p - 1.960 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.99.left <- (N * p - 2.576 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.95.right <- (N * p + 1.960 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

Z.99.right <- (N * p + 2.576 * sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N))

# calculate cum. probabilities for both binomial and normal distributions

y.binom <- pbinom(x, size=N, prob=p) * 100

y.norm <- pnorm(x, mean=N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100

# create data.table for plotting

dt <- data.table(x = x, y.binom = y.binom, y.norm = y.norm)

# calculate error

dt[, error := y.binom - y.norm]

# add hover text messages

dt[, text.1 := paste0(round(y.binom, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.2 := paste0(round(y.norm, 3), "%")]

dt[, text.3 := paste0(round(error, 3), "%")]

# create figure

fig <- plot_ly(data = dt, type = 'scatter', mode = 'lines')

# add traces

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~y.norm, text = ~text.1,

name = 'Normal',mode = 'lines',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "#FF6666", width = 5))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~y.binom, text = ~text.2,

name = 'Binomial',mode = 'markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

marker = list(color = "#3399FF", size = 12))

fig <- fig %>% add_trace(x = ~x, y = ~error, text = ~text.3,

name = 'Error',mode = 'lines+markers',

hoverinfo = 'text',

line = list(color = "black", width = 5),

marker = list(color = "black", size = 12))

# update layout

fig <- fig %>% layout(title = paste0("p = ", round(p*100, 1), "%, ", N, " trials (EV = ", x.ratio, ")"),

xaxis = list(title = "Observations"),

yaxis = list (title = "Probability, %"),

hovermode = "x unified",

shapes = list(vline(Z.99.left, color='red'), vline(Z.95.left), vline(Z.95.right), vline(Z.99.right, color='red')),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Distributions </b>')))

# return figure object

return(fig)

}

# plot example for 0.1%

PlotCumProbs(0.001, 5000)

```

## 10% (5 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 1%

PlotCumProbs(0.01, 500)

```

## 10% (10 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 10%

PlotCumProbs(0.1, 100)

```

## 20% (15 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 20%

PlotCumProbs(0.2, 75)

```

## 50% (5 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 50%

PlotCumProbs(0.5, 10)

```

## 50% (10 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 50%

PlotCumProbs(0.5, 20)

```

## 50% (15 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 50%

PlotCumProbs(0.5, 30)

```

## 80% (15 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 80%

PlotCumProbs(0.8, 75)

```

## 90% (10 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 90%

PlotCumProbs(0.9, 100)

```

## 99% (5 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 99%

PlotCumProbs(0.99, 500)

```

## 99.9% (5 EV)

```{r}

# plot example for 99.9%

PlotCumProbs(0.999, 5000)

```

:::

The first thing to note is that it's not possible to test a 2-sided hypothesis for a low EV example. Take a look at the tabs with "(5 EV)" in their name - the red dashed lines fall outside the range of viable outcomes, except for 50% (5EV) case. In this example, if you conduct 10 trials and observe either 0 or 10 successes, you can reject the null hypothesis $H_0 \ne p$ with a 99% confidence interval. However, as the sample size increases i.e. one gets larger EV, the distribution widths become narrower. This means that 2-sided tests with a 99% confidence interval become viable for other probability values, as seen in the example with an 20% (15 EV). Additionally, when comparing distributions with the same EV but different probabilities, we see that the error between the binomial distribution and its approximation using the normal distribution is very similar.

## Approximation error dynamics

Finally, let's now explore how much $ratio_1$ and total absolute approximation errors are affected by the sample size. In the examples below, the sample sizes were adjusted based on the number of expected successes/failures. For instance, to observe 5 EV with p=1%, one needs 500 observations and for p=20%, one needs 25 observations. However, this approach has some drawbacks, such as being difficult to normalize for specific cases. For example, to observe 7 EV with p=15%, one needs 46.66 observations. In such cases, the number of observations was rounded down to the nearest integer, resulting in some spiky line charts for these specific cases.

::: panel-tabset

## Ratio 1

```{r}

# generate data.table with expected values and sample probabilities

probs <- c(0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.99, 0.999)

dt <- CJ(Sucesses = c(1:50), p = probs)

# get probability and sample size for expected values

dt[p <= 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / p)]

dt[p > 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / (1 - p))]

# get number of failures

dt[, Failures := N - Sucesses]

# calculate probabilities to observe expected number of observations

dt[p <= 0.5, binom.p1 := dbinom(Sucesses, size = N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[p > 0.5, binom.p1 := dbinom(Failures, size = N, prob=p) * 100]

dt[p <= 0.5, norm.p1 := dnorm(Sucesses, mean = N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

dt[p > 0.5, norm.p1 := dnorm(Failures, mean = N * p, sd = sqrt(p * (1 - p) * N)) * 100]

# get ratio between point estimates

dt[, ratio.1 := round(binom.p1/norm.p1 * 100, 3)]

# for coloring get probability

dt[, Probability := paste0(round(p * 100, 1), "%")]

# text message for hover (decided not to use this column)

dt[, text := paste0(Probability, " with ", N, " attempts: ", ratio.1)]

# generate color palette

# code example taken from

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15282580/how-to-generate-a-number-of-most-distinctive-colors-in-r

n <- length(probs)

qual_col_pals = brewer.pal.info[brewer.pal.info$category == 'qual',]

col_vector = unlist(mapply(brewer.pal, qual_col_pals$maxcolors, rownames(qual_col_pals)))

# generate figure

fig <- plot_ly(dt,

x = ~Sucesses,

y = ~ratio.1,

color = ~Probability,

colors = col_vector,

line = list(width = 4))

fig <- fig %>% add_lines()

# with log scales

fig <- layout(fig,

hovermode = "x unified",

yaxis = list(type = "log", title = "Ratio 1, %"),

xaxis = list(title = "Expected sucessess/failures"),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Probabilities </b>')))

fig

```

## Approximation error

```{r}

# generate data.table with expected values and sample probabilities

probs <- c(0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.99, 0.999)

dt <- CJ(Sucesses = c(1:100), p = probs)

# get probability and sample size for expected values

dt[p <= 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / p)]

dt[p > 0.5, N := ceiling(Sucesses / (1 - p))]

# get number of failures

dt[, Failures := N - Sucesses]

# ugly, but quick way to calculate approximation error

for (idx in 1:nrow(dt)){

# generate vector

x.vect <- 0:dt[idx, N]

# select probaiblity

p.tmp <- dt[idx, p]

# get probabilities for both binomial and norm distributions

y.binom <- dbinom(x.vect, dt[idx, N], p.tmp)

y.norm <- dnorm(x.vect, mean=dt[idx, N] * p.tmp, sd = sqrt(p.tmp * (1 - p.tmp) * dt[idx, N]))

# sum absolute error

y.err <- sum(abs(y.binom - y.norm))

# add error term

dt[idx, tot.abs.error := round(y.err*100, 3)]

}

# generate color palette

# code example taken from

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15282580/how-to-generate-a-number-of-most-distinctive-colors-in-r

n <- length(probs)

qual_col_pals = brewer.pal.info[brewer.pal.info$category == 'qual',]

col_vector = unlist(mapply(brewer.pal, qual_col_pals$maxcolors, rownames(qual_col_pals)))

# for coloring get probability

dt[, Probability := paste0(round(p * 100, 1), "%")]

# generate figure

fig <- plot_ly(dt,

x = ~Sucesses,

y = ~tot.abs.error,

color = ~Probability,

colors = col_vector,

line = list(width = 4))

fig <- fig %>% add_lines()

# with log scales

fig <- layout(fig,

hovermode = "x unified",

yaxis = list(type = "log", title = "Total absolute error, %"),

xaxis = list(title = "Expected sucessess/failures"),

legend=list(title=list(text='<b> Probabilities </b>')))

fig

```

:::

Surprisingly the $ratio_1$ is inversely depended on probability - approximation error is the smallest for very likely or unluckily cases. The opposite is true for total absolute error - it is the smallest for p=50%. Even with 50 EV for small probabilities, i.e. 0.1% or 99.9% this error $>3.5\%$. The key take away is that if we are looking ar large confidence intervals (CI), i.e. 95% or 99%, then 10 EV is sufficient to test hypothesis. If we would like to establish some intermediate values between, then for small probabilities, number of observations to collect should increased.

## Conclusions

One should be very mindful when designing experiments for one-sample binomial test. Failing to meet "success-failure" condition would result in overestimation or underestimation of you $H_0$ hypothesis results. For relatively large probabilities, 30%-70% one can use

## References

Content for this blog post was prepared using following resources:

- https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/binomial-test-using-spss-statistics.php

- http://mlwiki.org/index.php/Binomial_Proportion_Tests

- https://sites.ualberta.ca/\~lkgray/uploads/7/3/6/2/7362679/slides\_-\_binomialproportionaltests.pdf

- https://www.technologynetworks.com/informatics/articles/the-binomial-test-366022

- https://towardsdatascience.com/turning-a-two-sample-event-rate-test-into-a-one-sample-binomial-test-23fbfb9d1df6

- https://www.studysmarter.us/explanations/math/statistics/binomial-hypothesis-test/

- https://www.statology.org/success-failure-condition/

- https://towardsdatascience.com/bernoulli-and-binomial-random-variables-d0698288dd36

- https://ubc-mds.github.io/DSCI_551_stat-prob-dsci/lectures/simulation.html

- https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1978138/probability-of-x-red-balls-when-drawing-y-balls-from-a-red-and-b-green-balls